The Child No One Wanted to Dispute, until Money Got Involved: The Legal Battle to Protect a Child’s Place in the Family.

Atty. Shiba Ashley Fernandez

Atty. Lea Mona Chu

Atty. Rhenelle Mae Operario

JANUARY 2026

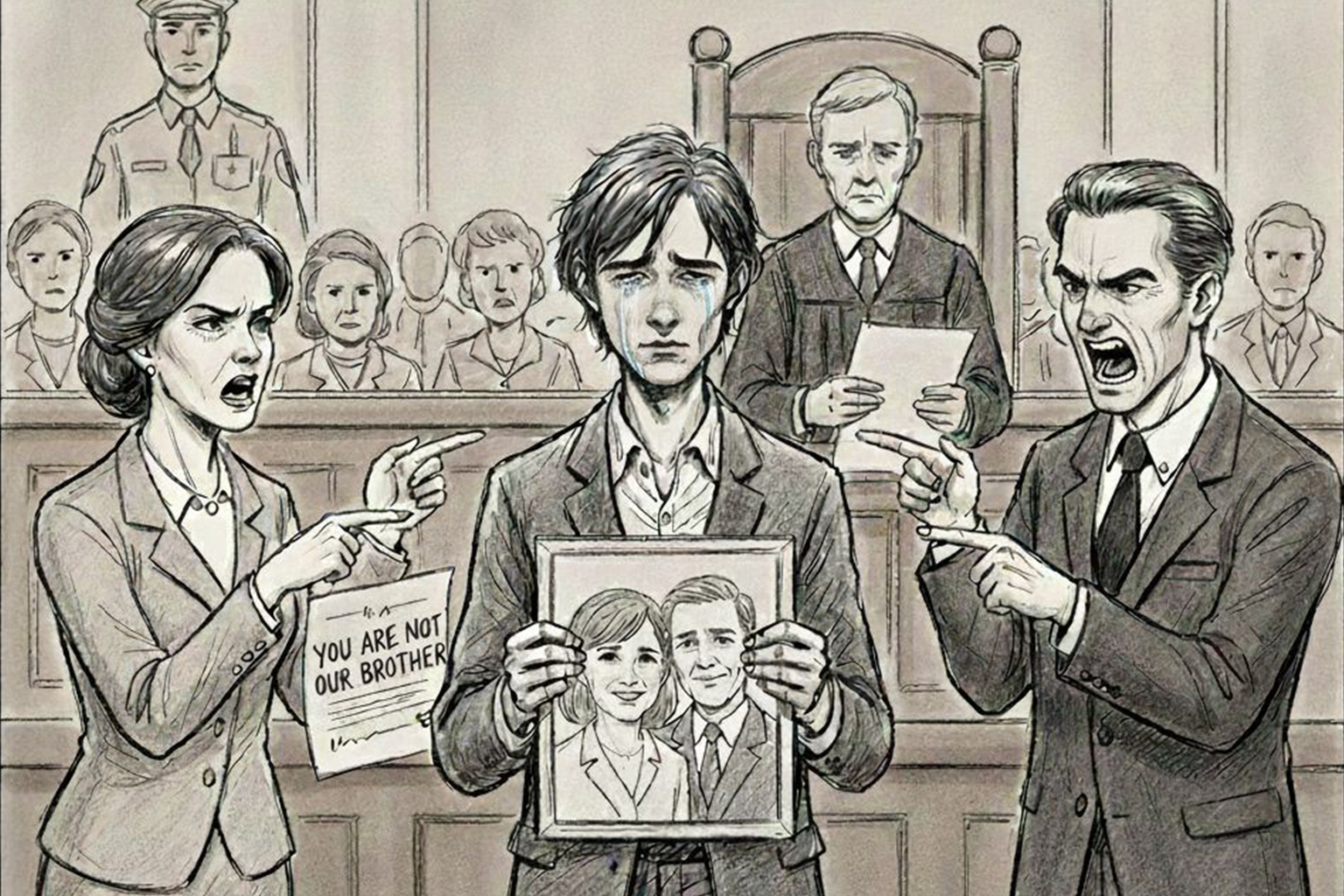

For as long as anyone could remember, Spouses Dela Cruz were known as the proud parents of Juan Dela Cruz (“Juan”). He was raised under their roof, surrounded by love and care,

bearing their surname, calling them Tatay and Nanay, and growing up alongside his half-siblings as part of one family. In school records, hospital forms, and even on his Certificate

of Live Birth, Juan was identified as their son. For many years, his filiation was never questioned, not by neighbors, not by relatives, and not even by the Spouses Dela Cruz themselves.

To everyone, Juan’s place in the family was unquestioned and undisputed.

When Spouses Dela Cruz died, grief filled the home before legal matters began. Soon, papers were filed, numbers were counted, and inheritance was discussed. The half-siblings from the father’s previous relationship returned not to mourn, but to claim their share of the estate. To them, Juan was no longer a brother but an obstacle. They claimed that Juan did not truly belong to the family, citing the absence of blood ties, and argued that a relationship long accepted should now be questioned in view of the impending division of the estate.

Acting on this claim, the half-siblings filed a petition in court seeking the cancellation of Juan’s Certificate of Live Birth, alleging that it had been falsified to make it appear that their father signed it. They likewise asked the court to order DNA testing to determine Juan’s filiation with their father.

This raises the question of whether a petition for the cancellation of a Certificate of Live Birth can be used to challenge a child’s filiation, and whether the parties involved may request the court to order DNA testing to establish such filiation.

What is filiation? The Supreme Court in Ko vs. Republic of the Philippines1 has ruled that “filiation is a relationship, the test of being someone’s offspring, which is determined mainly by biology. It may be the law that solely declares who are legitimate children, but in no way can it alter blood relationships.”

The Family Code contains specific provisions governing filiation, including the circumstances under which a person’s filiation may be challenged, the individuals who are legally entitled to contest a child’s filiation, and the types of evidence that may be presented to establish filiation. These apply to all children, whether legitimate, illegitimate, or legitimated, providing a legal framework to determine parentage and protect the rights of both children and parents.

Notably, Article 170 of the Family Code provides that only the husband or the putative father may challenge the legitimacy of a child within the time prescribed therein. In certain instances, however, Article 171 of Family Code allows the heirs of the husband or father to contest the child’s legitimacy, such as if the husband should die before the expiration of the period fixed for bringing his action, or if the child was born after the death of the husband, among others.

Applying the foregoing to the present scenario, the father did not file any action to challenge the legitimacy of Juan, nor did he initiate any proceeding indicating an intent to question Juan’s filiation. Consequently, the half-siblings, as the father’s heirs, are not entitled to contest Juan’s filiation, since the instances required under Article 171 of the Family Code are absent herein. Additionally, under the Rules of Court 2, “an interested person may file a petition for the cancellation of certificate of live birth under Rule 108 of the Rules of Court, which provides that “any person interested in any act, event, order or decree concerning the civil status of persons which has been recorded in the civil register, may file a verified petition for the cancellation or correction of any entry relating thereto, with the Court of First Instance of the province where the corresponding civil registry is located.” Accordingly, under Sec. 2 of Rule 108, the following entries may be subject to cancellation or correction, to wit:

When Spouses Dela Cruz died, grief filled the home before legal matters began. Soon, papers were filed, numbers were counted, and inheritance was discussed. The half-siblings from the father’s previous relationship returned not to mourn, but to claim their share of the estate. To them, Juan was no longer a brother but an obstacle. They claimed that Juan did not truly belong to the family, citing the absence of blood ties, and argued that a relationship long accepted should now be questioned in view of the impending division of the estate.

Acting on this claim, the half-siblings filed a petition in court seeking the cancellation of Juan’s Certificate of Live Birth, alleging that it had been falsified to make it appear that their father signed it. They likewise asked the court to order DNA testing to determine Juan’s filiation with their father.

This raises the question of whether a petition for the cancellation of a Certificate of Live Birth can be used to challenge a child’s filiation, and whether the parties involved may request the court to order DNA testing to establish such filiation.

What is filiation? The Supreme Court in Ko vs. Republic of the Philippines1 has ruled that “filiation is a relationship, the test of being someone’s offspring, which is determined mainly by biology. It may be the law that solely declares who are legitimate children, but in no way can it alter blood relationships.”

The Family Code contains specific provisions governing filiation, including the circumstances under which a person’s filiation may be challenged, the individuals who are legally entitled to contest a child’s filiation, and the types of evidence that may be presented to establish filiation. These apply to all children, whether legitimate, illegitimate, or legitimated, providing a legal framework to determine parentage and protect the rights of both children and parents.

Notably, Article 170 of the Family Code provides that only the husband or the putative father may challenge the legitimacy of a child within the time prescribed therein. In certain instances, however, Article 171 of Family Code allows the heirs of the husband or father to contest the child’s legitimacy, such as if the husband should die before the expiration of the period fixed for bringing his action, or if the child was born after the death of the husband, among others.

Applying the foregoing to the present scenario, the father did not file any action to challenge the legitimacy of Juan, nor did he initiate any proceeding indicating an intent to question Juan’s filiation. Consequently, the half-siblings, as the father’s heirs, are not entitled to contest Juan’s filiation, since the instances required under Article 171 of the Family Code are absent herein. Additionally, under the Rules of Court 2, “an interested person may file a petition for the cancellation of certificate of live birth under Rule 108 of the Rules of Court, which provides that “any person interested in any act, event, order or decree concerning the civil status of persons which has been recorded in the civil register, may file a verified petition for the cancellation or correction of any entry relating thereto, with the Court of First Instance of the province where the corresponding civil registry is located.” Accordingly, under Sec. 2 of Rule 108, the following entries may be subject to cancellation or correction, to wit:

Section 2. Entries subject to cancellation or correction. — Upon good and valid grounds, the following entries in the civil register may be cancelled or corrected: (a) births: (b) marriage; (c) deaths; (d) legal separations; (e) judgments of annulments of marriage; (f) judgments declaring marriages void from the beginning; (g) legitimations; (h) adoptions; (i) acknowledgments of natural children; (j) naturalization; (k) election, loss or recovery of citizenship; (l) civil interdiction; (m) judicial determination of filiation; (n) voluntary emancipation of a minor; and (o) changes of name.

In Eleosida et al. vs. Local Civil Registrar of Quezon City et al.3, the Supreme Court finds that “Rule 108 of the Revised Rules of Court provides the procedure for cancellation or correction of entries in the civil registry.

The proceedings under said rule may either be summary or adversary in nature. If the correction sought to be made in the civil register is clerical, then the procedure to be adopted is summary. If the rectification affects the

civil status, citizenship or nationality of a party, it is deemed substantial, and the procedure to be adopted is adversary.”

Given the foregoing, any person with a legitimate interest in having entries in the civil registry corrected or canceled may file the appropriate petition, either with the courts or directly with the civil registry, depending on the nature of the change sought. Whether the amendment involves a clerical error, a change in personal circumstances, or a challenge to filiation, the type of modification determines the proper forum for the petition, ensuring that the request follows the correct legal process while maintaining the integrity of the civil registry. In numerous cases, the Supreme Court has allowed such corrections when the parties were able to clearly demonstrate their necessity, recognizing that although civil registry records are generally presumed accurate, they may be amended if sufficient evidence proves the entries are erroneous. However, the Supreme Court has also emphasized in the case of Lee et al. vs. Lee et al.4 that the “legitimacy and filiation of children cannot be collaterally attacked in a petition for correction of entries in the certificate of live birth. A Petition for Correction whose commanding intent is to impugn a child’s filiation with a parent identified in the birth records – and not merely to harmonize those records with self-evident facts – will be disallowed for being such a collateral attack.”

Further, in Republic of the Philippines vs. Boquiren5, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled that “the legitimacy of a child cannot be collaterally attacked, and may be impugned only in a direct proceeding for that purpose: this doctrine applies in equal force to the impugnation of the status of ‘legitimated’ children.”

Applying the foregoing principles to the present scenario, the petition filed by the half-siblings was formally denominated as a “Petition for the Cancellation of the Certificate of Live Birth of Juan Dela Cruz”. Yet, a careful review of its allegations and objectives shows that its real purpose was to directly challenge Juan’s filiation. Such an attempt constitutes a collateral attack on the child’s legitimacy, which is prohibited under our laws. By disputing his status as a child of the deceased, the half-siblings essentially sought to disqualify him from inheritance and to bar him from claiming any portion of the estate they expected to inherit from their late father.

On another point, the half-siblings asked the Court to order DNA testing to prove that Juan is not biologically related to their late father. The question now arises: may the Court grant such a request? In Lee et al. vs. Lee et al.6, the Regional Trial Court denied the parties’ request for the conduct of DNA Testing as it amounted to a fishing expedition, as there appeared no independent evidence specifically pointing to a filial relationship, to wit:

Given the foregoing, any person with a legitimate interest in having entries in the civil registry corrected or canceled may file the appropriate petition, either with the courts or directly with the civil registry, depending on the nature of the change sought. Whether the amendment involves a clerical error, a change in personal circumstances, or a challenge to filiation, the type of modification determines the proper forum for the petition, ensuring that the request follows the correct legal process while maintaining the integrity of the civil registry. In numerous cases, the Supreme Court has allowed such corrections when the parties were able to clearly demonstrate their necessity, recognizing that although civil registry records are generally presumed accurate, they may be amended if sufficient evidence proves the entries are erroneous. However, the Supreme Court has also emphasized in the case of Lee et al. vs. Lee et al.4 that the “legitimacy and filiation of children cannot be collaterally attacked in a petition for correction of entries in the certificate of live birth. A Petition for Correction whose commanding intent is to impugn a child’s filiation with a parent identified in the birth records – and not merely to harmonize those records with self-evident facts – will be disallowed for being such a collateral attack.”

Further, in Republic of the Philippines vs. Boquiren5, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled that “the legitimacy of a child cannot be collaterally attacked, and may be impugned only in a direct proceeding for that purpose: this doctrine applies in equal force to the impugnation of the status of ‘legitimated’ children.”

Applying the foregoing principles to the present scenario, the petition filed by the half-siblings was formally denominated as a “Petition for the Cancellation of the Certificate of Live Birth of Juan Dela Cruz”. Yet, a careful review of its allegations and objectives shows that its real purpose was to directly challenge Juan’s filiation. Such an attempt constitutes a collateral attack on the child’s legitimacy, which is prohibited under our laws. By disputing his status as a child of the deceased, the half-siblings essentially sought to disqualify him from inheritance and to bar him from claiming any portion of the estate they expected to inherit from their late father.

On another point, the half-siblings asked the Court to order DNA testing to prove that Juan is not biologically related to their late father. The question now arises: may the Court grant such a request? In Lee et al. vs. Lee et al.6, the Regional Trial Court denied the parties’ request for the conduct of DNA Testing as it amounted to a fishing expedition, as there appeared no independent evidence specifically pointing to a filial relationship, to wit:

“x x x x the Regional Trial Court of Caloocan denied Rita et al.’s Motion. It reasoned that the DNA test they sought amounted to a fishing expedition, as there appeared no independent evidence specifically pointing to a filial relationship between Emma and Tiu:

This Court takes extreme caution and restraint in granting the prayed for DNA analysis, especially in this case where no evidence has yet been presented which would at least tend to establish any filial relationship between Emma Lee and Tiu Chua.

In the absence of any such evidence on Tiu, this Court supports respondents’ view that a DNA analysis on Tiu would be a “wild and unauthorized fishing expedition” which would tend to exploit, intrude into or violate Tiu’s right to privacy.”

This Court takes extreme caution and restraint in granting the prayed for DNA analysis, especially in this case where no evidence has yet been presented which would at least tend to establish any filial relationship between Emma Lee and Tiu Chua.

In the absence of any such evidence on Tiu, this Court supports respondents’ view that a DNA analysis on Tiu would be a “wild and unauthorized fishing expedition” which would tend to exploit, intrude into or violate Tiu’s right to privacy.”

In the abovementioned case, the Supreme Court acknowledged that DNA testing is a valid method for establishing paternity and filiation. However, the Court stressed that the mere reliability and

availability of DNA testing do not make it an automatic remedy that parties may obtain by judicial order at will or for mere convenience.

Additionally, in Deramas et al. vs. Hon. Galano et al.7 , the Court of Appeals held that, “the issuance of the DNA testing order remains discretionary upon the courts. It provided for instances that the courts may consider before granting a DNA testing order, such as, but not limited to, whether there is an absolute necessity for the DNA testing. However, if there is already preponderance of evidence to establish paternity and the DNA test result will only be corroborative, then the courts, in its discretion, disallow DNA testing.” Ultimately, the Court of Appeals, denied the motion for DNA testing as the grounds relied to by the requesting party were premised solely on such tenuous or insubstantial grounds.

Applying this doctrine to the scenario, the half-siblings cannot compel the court to order DNA testing just based on their claim that Juan is not biologically related to their late father. The law requires more than an allegation; there must be evidence that their father ever questioned Juan’s filiation or took steps to challenge it. Without such proof, the court is not required to allow DNA testing, since the claim is based on speculation rather than a real need to resolve a dispute over filiation.

In reality, a child’s status is often placed in a precarious position whenever family disputes over wealth and inheritance arise. Conflicts over money can easily turn into attempts to question the legitimacy or filiation of a child, even when there has been no previous doubt about their parentage. Recognizing the potential harm to the child’s welfare and the disruption such claims can cause, the courts strongly discourage and may outright reject petitions that are unfounded, malicious, or filed merely to challenge someone’s filiation for personal gain.

Such actions are viewed not only as legally improper but also as morally objectionable, as they exploit the legal system to undermine family relationships and create unnecessary conflict. Ultimately, the law seeks to protect the child’s status, maintain the integrity of familial bonds, and prevent the courts from being used as a tool for opportunistic or vindictive claims.

Additionally, in Deramas et al. vs. Hon. Galano et al.7 , the Court of Appeals held that, “the issuance of the DNA testing order remains discretionary upon the courts. It provided for instances that the courts may consider before granting a DNA testing order, such as, but not limited to, whether there is an absolute necessity for the DNA testing. However, if there is already preponderance of evidence to establish paternity and the DNA test result will only be corroborative, then the courts, in its discretion, disallow DNA testing.” Ultimately, the Court of Appeals, denied the motion for DNA testing as the grounds relied to by the requesting party were premised solely on such tenuous or insubstantial grounds.

Applying this doctrine to the scenario, the half-siblings cannot compel the court to order DNA testing just based on their claim that Juan is not biologically related to their late father. The law requires more than an allegation; there must be evidence that their father ever questioned Juan’s filiation or took steps to challenge it. Without such proof, the court is not required to allow DNA testing, since the claim is based on speculation rather than a real need to resolve a dispute over filiation.

In reality, a child’s status is often placed in a precarious position whenever family disputes over wealth and inheritance arise. Conflicts over money can easily turn into attempts to question the legitimacy or filiation of a child, even when there has been no previous doubt about their parentage. Recognizing the potential harm to the child’s welfare and the disruption such claims can cause, the courts strongly discourage and may outright reject petitions that are unfounded, malicious, or filed merely to challenge someone’s filiation for personal gain.

Such actions are viewed not only as legally improper but also as morally objectionable, as they exploit the legal system to undermine family relationships and create unnecessary conflict. Ultimately, the law seeks to protect the child’s status, maintain the integrity of familial bonds, and prevent the courts from being used as a tool for opportunistic or vindictive claims.

DISCLAIMER: The scenario presented is entirely fictional and is not based on real persons, events, or cases. Any resemblance or connection, whether direct or indirect, to actual persons, events, or cases is purely coincidental.