When the Merriest Season Ends in Silence: : Understanding Succession Law

Atty. Donna Mae Pearl C. Dumaliang

Atty. Rhenelle Mae O. Operario

DECEMBER 2025

FFor us Filipinos, December is a season of warmth, family reunions, and endless celebrations. It is when homes are filled with laughter,

tables with food, and hearts with hope. Yet, as health studies and experts warn, it is also a month marked by sudden loss.

A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association and the British Medical Journal revealed that more people die from heart attacks during the last week of December than at any other time of the year. As health reform advocate Dr. Anthony Leachon once said, “December is the merriest time of the year, but also the deadliest time of the year.” 1

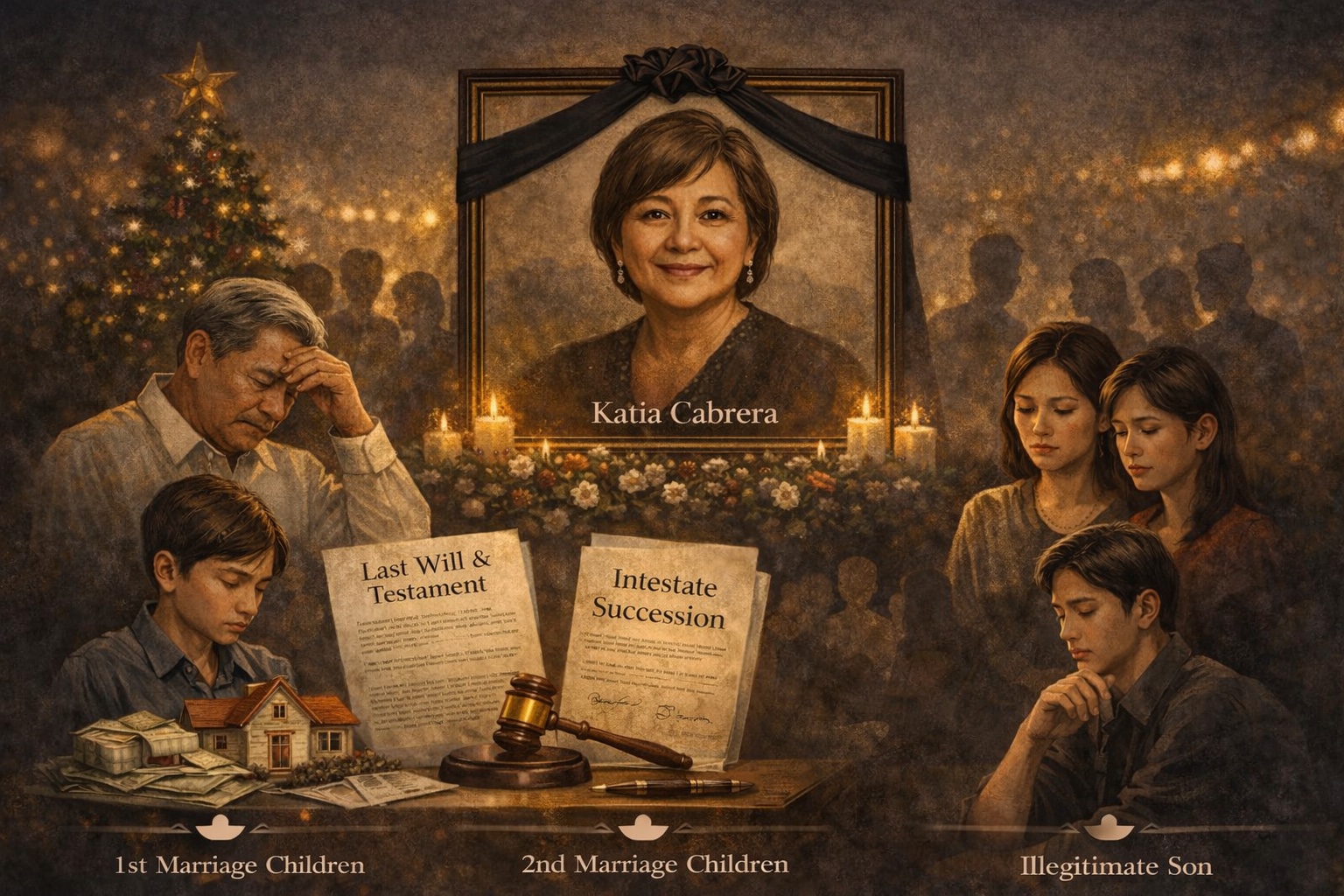

For one family, that warning became painfully real. Just days before Christmas, as cheerful voices filled the air and the festive lights flickered in quiet corners of every Filipino home, Katia Cabrera, a 61-year-old former undersecretary at a prominent government agency and a woman of considerable wealth and impeccable reputation, suddenly died without a warning. Joy turned to mourning in an instant.

She left behind a sizable estate, a surviving husband, and six children – three (3) from her first marriage, two (2) from her second and one (1) illegitimate child whose place in the family had never been openly acknowledged. The family gathered in shock, unsure of what would come next.

In the silence that followed, questions began to surfaced: Who would inherit her sizable estate? Would all her children be treated equally? And what about decisions that needed to be made for the family she suddenly left behind?

Settling the estate of a deceased loved one is never a simple task. It involves navigating complex legal procedures, each carrying important consequences and delicate considerations. Within this framework, two main paths exist for distributing decedent’s properties: (1) Testamentary and (2) Legal or Intestate Succession.2 Each has its own set of advantages and challenges, making it essential for individuals and families to understand their implications, especially in situations like that of Katia Cabrera, where multiple heirs and blended family dynamics are involved.

In Testamentary Succession, the decedent leaves a valid will, which may either be a Notarial Will or a Holographic Will, specifying how their estate should be distributed among heirs. A Notarial Will is a formal document prepared with the assistance of witnesses and executed before a notary public, ensuring its authenticity and legal recognition,3 while a Holographic Will is one which is entirely written, dated, and signed by the testator, requiring no notarization but still subject to strict legal requirements.4

The requisites of a valid will in the Philippines are governed by Title IV, Chapter 2 of the Civil Code of the Philippines. Among the different types of wills, the Notarial Will is the most commonly used due to its reliability and formal recognition by the courts. The essential requirements for a Notarial Will are as follows:

A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association and the British Medical Journal revealed that more people die from heart attacks during the last week of December than at any other time of the year. As health reform advocate Dr. Anthony Leachon once said, “December is the merriest time of the year, but also the deadliest time of the year.” 1

For one family, that warning became painfully real. Just days before Christmas, as cheerful voices filled the air and the festive lights flickered in quiet corners of every Filipino home, Katia Cabrera, a 61-year-old former undersecretary at a prominent government agency and a woman of considerable wealth and impeccable reputation, suddenly died without a warning. Joy turned to mourning in an instant.

She left behind a sizable estate, a surviving husband, and six children – three (3) from her first marriage, two (2) from her second and one (1) illegitimate child whose place in the family had never been openly acknowledged. The family gathered in shock, unsure of what would come next.

In the silence that followed, questions began to surfaced: Who would inherit her sizable estate? Would all her children be treated equally? And what about decisions that needed to be made for the family she suddenly left behind?

Settling the estate of a deceased loved one is never a simple task. It involves navigating complex legal procedures, each carrying important consequences and delicate considerations. Within this framework, two main paths exist for distributing decedent’s properties: (1) Testamentary and (2) Legal or Intestate Succession.2 Each has its own set of advantages and challenges, making it essential for individuals and families to understand their implications, especially in situations like that of Katia Cabrera, where multiple heirs and blended family dynamics are involved.

In Testamentary Succession, the decedent leaves a valid will, which may either be a Notarial Will or a Holographic Will, specifying how their estate should be distributed among heirs. A Notarial Will is a formal document prepared with the assistance of witnesses and executed before a notary public, ensuring its authenticity and legal recognition,3 while a Holographic Will is one which is entirely written, dated, and signed by the testator, requiring no notarization but still subject to strict legal requirements.4

The requisites of a valid will in the Philippines are governed by Title IV, Chapter 2 of the Civil Code of the Philippines. Among the different types of wills, the Notarial Will is the most commonly used due to its reliability and formal recognition by the courts. The essential requirements for a Notarial Will are as follows:

a) Legal Capacity of the Testator

• The Testator must be in the age of Majority – 18 years old. 5

• The Testator must be of sound mind at the time of the making of the will.6

• To be of sound mind, it is sufficient if the testator was able at the time of making the will to know the nature of the estate to be disposed of, the proper objects of his or her bounty, and the character of the testamentary act.7

b) Form

• Notarial Wills must be made in writing and can either be handwritten or typewritten.8 It must be signed by the testator or by the testator’s name written by some other person in his presence, and by his express direction.9

• All pages of the will shall be numbered correlatively in letters placed on the upper part of each page.10

c) Language Requirements

• Every will must be executed in a language or dialect known to the testator.11

d) Signature and Witness Requirements

• The testator must sign at the end of the will.12

• The testator must also acknowledge the will in the presence of three (3) credible witnesses, who must also sign the will in the presence of the testator and of each other.13

• The witnesses and testator must sign each and every page of the will, on the left margin, except the last.14

• The witnesses must be of sound mind, legal age, and not otherwise disqualified by law.15 Certain individuals, such as those named beneficiaries in the will16, those persons not domiciled in the Philippines, convicted of falsification of document, perjury or false testimony,17 may not serve as witnesses to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

e) Attestation Clause

• Attestation clause must be signed by the witnesses, which confirms that the testator signed the will in their presence, the testator declared it to be his or her last will and testament, and that they observed the testator signing with full mental faculties and voluntary intent.18

• If the language of the attestation clause is in a language not known to the witnesses, it shall be interpreted to them.19

f) Notarization Requirement

• The will must be acknowledged before a notary public, affirming that the testator and witnesses executed the said document freely and with full awareness.20

g) Probate Requirement

• A notarial will, as with any will, must undergo Probate Proceedings, which is also known as a judicial proceeding where the Court confirms the authenticity and due execution of the will. Without a probate, the will has no legal effect.21

• The Testator must be in the age of Majority – 18 years old. 5

• The Testator must be of sound mind at the time of the making of the will.6

• To be of sound mind, it is sufficient if the testator was able at the time of making the will to know the nature of the estate to be disposed of, the proper objects of his or her bounty, and the character of the testamentary act.7

b) Form

• Notarial Wills must be made in writing and can either be handwritten or typewritten.8 It must be signed by the testator or by the testator’s name written by some other person in his presence, and by his express direction.9

• All pages of the will shall be numbered correlatively in letters placed on the upper part of each page.10

c) Language Requirements

• Every will must be executed in a language or dialect known to the testator.11

d) Signature and Witness Requirements

• The testator must sign at the end of the will.12

• The testator must also acknowledge the will in the presence of three (3) credible witnesses, who must also sign the will in the presence of the testator and of each other.13

• The witnesses and testator must sign each and every page of the will, on the left margin, except the last.14

• The witnesses must be of sound mind, legal age, and not otherwise disqualified by law.15 Certain individuals, such as those named beneficiaries in the will16, those persons not domiciled in the Philippines, convicted of falsification of document, perjury or false testimony,17 may not serve as witnesses to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

e) Attestation Clause

• Attestation clause must be signed by the witnesses, which confirms that the testator signed the will in their presence, the testator declared it to be his or her last will and testament, and that they observed the testator signing with full mental faculties and voluntary intent.18

• If the language of the attestation clause is in a language not known to the witnesses, it shall be interpreted to them.19

f) Notarization Requirement

• The will must be acknowledged before a notary public, affirming that the testator and witnesses executed the said document freely and with full awareness.20

g) Probate Requirement

• A notarial will, as with any will, must undergo Probate Proceedings, which is also known as a judicial proceeding where the Court confirms the authenticity and due execution of the will. Without a probate, the will has no legal effect.21

While the Notarial Will remains the most commonly used due to its formal recognition and reliability, Philippine law also recognize the Holographic Will, the essential requisites of which are as follows:

a) Entirely Handwritten

• The Holographic Will must be entirely written, dated and signed by the hand of the testator.22 Typewritten, printed, or partly handwritten will are not considered holographic.23

b) No witness requirement

• No witnesses are necessary for Holographic Will.

c) Complete date

• The date of the will must be complete (day, month, and year).

d) Signature placement

• The testator must sign at the end of the will. Any disposition written after the signature is generally considered void and shall not be given effect, unless it is clearly shown that the testator intended such disposition to form part of the will, and the same is duly dated and signed by the testator.24

e) Probate requirement

• In the probate of a holographic will, it shall be necessary that at least one (1) witness who knows the handwriting and signature of the testator explicitly declare that the will and the signature are in the handwriting of the testator. If the will is contested, at least three (3) of such witnesses shall be required.25

• In absence of any competent witness, and if the court deem it necessary, expert testimony may be resorted to.26

• The Holographic Will must be entirely written, dated and signed by the hand of the testator.22 Typewritten, printed, or partly handwritten will are not considered holographic.23

b) No witness requirement

• No witnesses are necessary for Holographic Will.

c) Complete date

• The date of the will must be complete (day, month, and year).

d) Signature placement

• The testator must sign at the end of the will. Any disposition written after the signature is generally considered void and shall not be given effect, unless it is clearly shown that the testator intended such disposition to form part of the will, and the same is duly dated and signed by the testator.24

e) Probate requirement

• In the probate of a holographic will, it shall be necessary that at least one (1) witness who knows the handwriting and signature of the testator explicitly declare that the will and the signature are in the handwriting of the testator. If the will is contested, at least three (3) of such witnesses shall be required.25

• In absence of any competent witness, and if the court deem it necessary, expert testimony may be resorted to.26

Having discussed the rules and formalities governing testamentary succession, it is important to note that the distribution of properties under a valid will is controlling only within the limits prescribed by law. In the Philippines, certain heirs, called compulsory heirs, are entitled by law to a fixed portion of the estate known as their legitime.27

In the case of Macalinao, et al. v. Macalinao, et al., G.R. No. 250613, 03 April 2024, the Supreme Court emphasized that the preservation of the legitime of compulsory heirs is imperative. This principle, as echoed by Justice Jurado, stands as the paramount consideration in the distribution of hereditary shares, to wit:

In the case of Macalinao, et al. v. Macalinao, et al., G.R. No. 250613, 03 April 2024, the Supreme Court emphasized that the preservation of the legitime of compulsory heirs is imperative. This principle, as echoed by Justice Jurado, stands as the paramount consideration in the distribution of hereditary shares, to wit:

“It must be noted, however, that in distributing the estate in accordance with the above proportions, one very fundamental rule must be observed. The legitime of compulsory heirs must never be impaired. Under our system of compulsory succession, whether testamentary or intestate, it is axiomatic that the legitime of compulsory heirs must be preserved. As a rule, it cannot be impaired by the will of the decedent whether expressed or presumed. (Emphasis supplied)

But what happens when a person dies without leaving a valid will? In such cases, the estate is distributed according to the rules of Legal or Intestate Succession28, as governed by Title IV, Chapter 3 of the Civil Code of the Philippines.

Unlike Testate Succession, where the decedent’s wishes guide the distribution of property, intestate succession relies entirely on statutory rules. This means that the rules on Intestate Succession decides who inherits, in what order, and in what share,29 which sometimes creates tensions among heirs, especially in blended families.

The persons entitled to inherit in cases of legal or intestate succession are determined by who survives the decedent and the degree of their relationship to him or her. Philippine law follows an order of preference based on proximity, excluding more remote relatives when nearer heirs exist. The following outlines the usual situations and the corresponding order of heirs:

Unlike Testate Succession, where the decedent’s wishes guide the distribution of property, intestate succession relies entirely on statutory rules. This means that the rules on Intestate Succession decides who inherits, in what order, and in what share,29 which sometimes creates tensions among heirs, especially in blended families.

The persons entitled to inherit in cases of legal or intestate succession are determined by who survives the decedent and the degree of their relationship to him or her. Philippine law follows an order of preference based on proximity, excluding more remote relatives when nearer heirs exist. The following outlines the usual situations and the corresponding order of heirs:

a) Legitimate Descendants

Legitimate children and their legitimate descendants are called to the inheritance first. They succeed either in their own right, where each child receives an equal share, or by right of representation, when a child has predeceased the decedent and his or her descendants take the share that would have belonged to their parent. 30

b) Legitimate Parents and Other Ascendants

In the absence of legitimate descendants, the legitimate parents inherit the estate in equal portions. If both parents are no longer living, the inheritance passes to the nearest ascendants in the direct line. Ascendants from the paternal and maternal lines succeed equally. 31

c) Illegitimate Children

Where there are no legitimate descendants, parents, or ascendants, illegitimate children inherit the entire estate in equal shares. If they inherit together with legitimate children, illegitimate children are entitled to a portion equivalent to one-half of the share of a legitimate child. 32

d) Surviving Spouse

The surviving spouse inherits together with other compulsory heirs, depending on the combination of survivors. When there are legitimate children, the spouse receives a share equal to that of one legitimate child. When concurring with legitimate parents or ascendants, the spouse is entitled to one-half of the estate. When the spouse inherits with illegitimate children, the estate is divided equally among them. In the absence of any other heirs, the surviving spouse succeeds to the entire estate.33

e) Brothers, Sisters, and Their Descendants

If the decedent leaves no descendants, ascendants, illegitimate children, or surviving spouse, the inheritance passes to the brothers and sisters and, where applicable, to their descendants. Siblings of the full blood are entitled to twice the share of those of the half blood. If a brother or sister predeceased the decedent, his or her children inherit by representation.34

f) Other Collateral Relatives

Should there be no brothers or sisters or their descendants, the estate devolves upon the nearest collateral relatives within the fifth degree of consanguinity, such as uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, and cousins.35

g) The State

In the absence of any heirs within the fifth degree of relationship, the estate escheats in favor of the State, which is mandated by law to apply the property or its proceeds to charitable or educational purposes.36

Legitimate children and their legitimate descendants are called to the inheritance first. They succeed either in their own right, where each child receives an equal share, or by right of representation, when a child has predeceased the decedent and his or her descendants take the share that would have belonged to their parent. 30

b) Legitimate Parents and Other Ascendants

In the absence of legitimate descendants, the legitimate parents inherit the estate in equal portions. If both parents are no longer living, the inheritance passes to the nearest ascendants in the direct line. Ascendants from the paternal and maternal lines succeed equally. 31

c) Illegitimate Children

Where there are no legitimate descendants, parents, or ascendants, illegitimate children inherit the entire estate in equal shares. If they inherit together with legitimate children, illegitimate children are entitled to a portion equivalent to one-half of the share of a legitimate child. 32

d) Surviving Spouse

The surviving spouse inherits together with other compulsory heirs, depending on the combination of survivors. When there are legitimate children, the spouse receives a share equal to that of one legitimate child. When concurring with legitimate parents or ascendants, the spouse is entitled to one-half of the estate. When the spouse inherits with illegitimate children, the estate is divided equally among them. In the absence of any other heirs, the surviving spouse succeeds to the entire estate.33

e) Brothers, Sisters, and Their Descendants

If the decedent leaves no descendants, ascendants, illegitimate children, or surviving spouse, the inheritance passes to the brothers and sisters and, where applicable, to their descendants. Siblings of the full blood are entitled to twice the share of those of the half blood. If a brother or sister predeceased the decedent, his or her children inherit by representation.34

f) Other Collateral Relatives

Should there be no brothers or sisters or their descendants, the estate devolves upon the nearest collateral relatives within the fifth degree of consanguinity, such as uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, and cousins.35

g) The State

In the absence of any heirs within the fifth degree of relationship, the estate escheats in favor of the State, which is mandated by law to apply the property or its proceeds to charitable or educational purposes.36

Once the heirs are identified under the intestate succession, the estate can be settled. If all debts and obligations have been fully paid, they may proceed with an extrajudicial settlement,

dividing the properties among themselves without first securing letters of administration. This is done by executing a public instrument filed with the Registry of Deeds, which legally

formalizes the transfer of ownership. Should the heirs fail to agree on the division, the matter may instead be resolved through an ordinary action for partition in court.

37

Ultimately, how an estate is distributed will depend on the wishes of the decedent. Every Filipino, at some point, will face the inevitability of death, and the law provides guidance to ensure that property and possessions are divided in accordance with the decedent’s intentions. These rules and procedures exist to make the process clear, fair, and manageable, offering a framework that has been designed with Filipino families in mind, so that everyone’s rights are respected and supported.

But for Katia Cabrera, her approach went beyond merely following the law. She had thoughtfully prepared her affairs, ensuring that her Last Will and Testament clearly reflected her wishes and that each of her children, her spouse, and even the often-overlooked members of her family were remembered and provided for.

Alongside her will, she left a single letter addressed to all her children and husband, written in her own hand, meant to be read when she could no longer speak for herself. It read:

Ultimately, how an estate is distributed will depend on the wishes of the decedent. Every Filipino, at some point, will face the inevitability of death, and the law provides guidance to ensure that property and possessions are divided in accordance with the decedent’s intentions. These rules and procedures exist to make the process clear, fair, and manageable, offering a framework that has been designed with Filipino families in mind, so that everyone’s rights are respected and supported.

But for Katia Cabrera, her approach went beyond merely following the law. She had thoughtfully prepared her affairs, ensuring that her Last Will and Testament clearly reflected her wishes and that each of her children, her spouse, and even the often-overlooked members of her family were remembered and provided for.

Alongside her will, she left a single letter addressed to all her children and husband, written in her own hand, meant to be read when she could no longer speak for herself. It read:

“If you are reading this, it means I am no longer there to hug you, to laugh with you, or to sit beside you during Christmas dinners. But please know that not a day passed when I did not think of all of you. Everything I have worked for, I built with you in mind. I hope what I leave behind will ease your worries, not create them. Share, forgive, and take care of one another for me. Celebrate your birthdays, your anniversaries, and every Christmas with joy, even without me. I will always be there, loving you in ways you cannot see.”

In that letter, Katia said the things every mother and wife hopes will be remembered long after she is gone. And so, while the merriest season turned silent with her passing, the silence was not empty. It was filled with her voice, her intentions, and her love, lingering in every room like the warmth of Christmas lights that continue to glow even after the night has grown still.

FOOTNOTES

1. Baclig, C. (2022, December 13). Merriest yet deadliest: Knowing and preventing holiday hazards. Retrieved from Inquirer.NET: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1704722/merriest-yet-deadliest-knowing-and-preventing-holiday-hazards

*The views and opinions expressed are based on applicable laws, constitutional provisions, and/or jurisprudence in force at the time of writing, and do not constitute legal advice or an official stance on any political matter. Subsequent legal or factual developments may affect the relevance or applicability of the views and opinions herein expressed.